Anna Borou Yu Portfolio

Anna Borou Yu creates and curates multimedia artworks in the forms of performance, installation, exhibition, film, VRAR, digital publication, and immersive theater. She reflects on the concept of body and space throughout history in different cultures, crafts embodied exhibition and cognitive performance in extended reality, and translates cultural heritage into contemporary interpretation with cutting edge technology.

1

CAVE DANCE_Bodyless Body

Harvard FAS CAMLab Project Role: Project Lead, Research, Tech Lead, Performance, Choreography, Exhibition Design Advisor: Prof. Eugene Wang 2021.7 - 2023.7

One of the most significant cultural heritage sites in the world, Dunhuang preserves more than 400 embellished Buddhist cave shrines dating from the fifth century to the fourteenth century. Covered with murals and sculptures, these cave shrines enclose visitors with an imaginary landscape of Buddhist legends and paradises. Standing out from the rich visual culture of the Dunhuang caves, scenes of celestial dance performances in Buddhist paradises are widely acclaimed as the most representative of artistic achievements at Dunhuang. Among the massive artworks, the figures in the murals of the Dance and Music Bodhisattva, Flying Apsaras, Vajra, and Lotus Children are particularly noteworthy.

Based upon interdisciplinary research on the Buddhist culture of dance in Dunhuang, the Cave Dance project harnesses the power of cutting edge technology to bring new insights into the ancient dance forms, and breathes new life into static dance paintings and translates ancient texts. We propose a systematic and interdisciplinary approach to the digitization, preservation, reconstruction and inmagination of Chinese classical Dunhuang dance.

The contributions are as follows:

(1) The first comprehensive Dunhuang dance motion capture dataset. We captured full-body performances by professional Dunhuang dancers in 11 sequences, totaling 40 minutes of high-quality data. The dataset contains skeleton, mesh, and video data, which is compatible with other common motion capture datasets and can be used for various applications.

(2) A technical pipeline that supports the reimagination of Dunhuang dance. We applied motion inbetweening and retiming methods to concatenate different dance segments and synchronized them with the background music. This enables the visualization of digital dancers and special effects that dancers cannot accomplish in real life.

(3) A collaborative framework that bridges the gap between dance and computing communities. Our research facilitated interdisciplinary dialogue and collaboration between professional dance researchers and computer scientists. This prompted a series of experiments including motion inbetweening, dance retargeting, and particle effects enabled by our dataset.

(4) An immersive new media exhibition that promotes the preservation of intangible cultural heritage.

project workflow VIDEO

project is composed of 3 core components: Motion capture, data processing and applications.

particle effects produced in unity, open frameworks, houdini, emergen

Beyond creating dance sequences in heaven synchronized with music, we also envisioned other visual effects to further explore the value of our dataset. While our current data format only includes human skeletons and template meshes in BVH and SMPL formats, we wanted to present the beauty of Dunhuang dance to the public in a more vivid and artistic way. To achieve this, we integrated various particle effects across multiple platforms, combining the digitized Dunhuang dance with modern VFX technology to showcase the aesthetic appeal of Chinese dance in a creative way. OpenFrameworks was employed to connect the BVH Joints with lines in every frame and created a stickfigure motion overlay effect, further enhancing the dynamism and visual interest of the dance. This technique complemented the previous particle effects and contributed to a multi-layered visual experience.

3D PRINTED MOTION SEQUENCE AND PROJECTION MAPPING

I also 3d printed the motion sequence model with resin into a translucent sculpture. With projection mapping, it emphasizes the fluidity and dynamic of the dance motion.

cave dance Immersive Experience

Flowering from the diverse body of research of this interdisciplinary project, Cave Dance manifests as a set of digital installations that elucidate the multifold culture of dance in Buddhist cave shrines. The exhibition not only immerses the audiences in a dynamic world of Dunhuang dance, but also leads them into the deeper cultural dimension of Buddhist dance—where audiences are invited to contemplate the themes of body, life, and spiritual transcendence embodied by the celestial dance in the cave.

cave dance COLLECTIVE MINDS

cave dance multiDISCIPLINARY TEAM

As the Project Lead of Cave Dance, I worked with over 50 scholars with expertise in art history, dance, design, architecture, computer science, and photography around the world, from New York, Boston, to Beijing and London. We also collaborated with renowned research institutes, technology lab and production companies, including Dunhuang Academy, MIT Immersion Lab, Barnard College Movement Lab, Beijing Dance Academy, etc. Our multidisciplinary methodology involves co-creation through a research-tech-design-exhibition roadmap, and a continuous dialogue that draws inspiration from diverse fields.

2

Translation Between Dance and Music

Yale Department of Music Class Project Role: Project Lead Collaborator: Jiajian Min Advisor: Prof. Konrad Kaczmarek 2020.1 - 2020.12

Published by ACM SIGGRAPH Asia Poster 2020

Translation between Dance and Music is an exploration on the translation between different art types, based on the Ballet Giselle. Here physical movement is adopted into digital signal and sound.

Always performed together, music and dance share similarities and correspondences. However, the relationship between these two art types have remained mysterious. This project is exploring an innovative strategy of deeper engagement between music and dance.In this project, a 1-minute clip from the ballet Giselle Act I (Scene 1.7 Peasant Pas de Deux, Male 1st Variation) is analyzed, and new music clips are generated and developed.

Historically, music notation and dance/movement notations are developed into various branches, from graphical and gurative to abstract and numerical, which seems incomparable. Luckily, the ballet Giselle is well archived, for which the music notation and the Benesh Dance Notation are both documented on the systematic structure of five-line stave, providing a similar visual image of ergonomically ideal matrix and securing an identical rhythm framework. In this project, a 1-minute clip from the ballet Giselle Act I (Scene 1.7 Peasant Pas de Deux, Male 1st Variation) is analyzed, and new music clips are generated and developed.

The expected outcome of the project is a New Symphony, laying all the music clips together based on the timeline of performance. The various music clips include Music 1: original music (played from music notation); Music 2: generated from the dancer motion (processed by software); and Music 3: generated from dance notation (visually translated to music notation and played).

Music 2 (motion captured and processed by algorithm): Several dancers are invited to perform, based on the dance notation and video documentations. The movement is motion captured by a Kinect XBox 360 and processed into digital signals by the music software MAX/MSP. Each time the movement is documented into two sets of waves according to the Benesh Notation principles: Music 2.1 a 5-buffer head/shoulders/waist/knees/feet body position wave, and Music 2.2 a 4-bu er hands/feet movement wave.

Music 3 (visually mapped from dance notation to music notation): The dance notation corresponds to the original music by respecting the rhythm and phrasing signs in the dance notation, and matches with original timing. At the same time, the symbols for body parts in dance notation are visually mapped to the music stave in corresponding place, with a similar thought in Music 2 processing. Also, the Music 3 is further detached as Music 3.1 (position frame) and Music 3.2 (hands/feet move Lines).

The Final result is a New Symphony, laying all the music channels together: Music 1.0 (original music), Music 2.1+Music 2.2 (from dance), and Music 3.1+Music 3.2 (from dance notation).

3

DAMUS: A Collaborative System For Choreography And Music Composition

Role: Project Lead Collaborators: Tiange Zhou, Zeyu Wang, Jiajian Min 2021.9 - 2023.11

Published by 2022 IEEE AIART Workshop, Featured at 2022 IRCAM Forum at NYU, Shanghai Power Station of Art, Sponsored by Beijing Normal University "Future Design Seed Fund"

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9859441 https://forum.ircam.fr/article/detail/damus-a-collaborative-system-for-choreography-and-music-composition/

Throughout the history of dance and music collaborations, composers and choreographers have always engaged in separate workflows. Usually, composers and choreographers complete the music and choreograph the moves separately, where the lack of mutual understanding of their artistic approaches results in a long production time. There is a strong need in the performance industry to reduce the time for establishing a collaborative foundation, allowing for more productive creations. We propose DAMUS, a work-in-progress collaborative system for choreography and music composition, in order to reduce production time and boost productivity. DAMUS is composed of a dance module DA and a music module MUS. DA translates dance motion into MoCap data, Labanotation, and number notation, and sets rules of variations for choreography. MUS produces musical materials that fit the tempo and rhythm of specific dance genres or moves. We applied our system prototype to case studies in three different genres. In the future, we plan to pursue more genres and further develop DAMUS with evolutionary computation and style transfer.

Index Terms— choreography, music composition, collaborative system

1. INTRODUCTION

We present a work-in-progress project named DAMUS, a collaborative modular and data-driven system that aims to algorithmically support the composers and choreographers to generate

original and diverse development for their creative variations and continuities. The project name DAMUS means “we offer” in Latin. Meanwhile, it is also a combined terminology with DA, the dance module, and MUS, the music module. Conventional dance-music collaborations regularly

take a significant amount of time for collaborators to adapt to one other’s creative languages; occasionally, collaborations can become overly exclusive, resulting in collaborations between only certain artistic groups. Nowadays, fastpaced productions and more inclusive creative collaboration environments necessitate an efficient solution that can preserve a significant amount of artistic authenticity while also facilitating rapid “brainstorming.” DAMUS, the compound collaborative authoring system, aims to build a collaborative foundation for choreographers and composers through algorithms. Using DAMUS will reduce time consumption on communication and motivate dynamic expressions by treating their complete or scattered creative ideas as preliminary units. We leverage machine learning, evolutionary computation, and creative constraints to produce dance and music variations either

for a single user or for multiple users, where they can interact with each other and express themselves dynamically. We will present details of our system design, data collection, the DAMUS components (the dance module and the music module), as well as the underlying logic for each. Furthermore, we would like to share our preliminary creative outputs through case studies involving three distinct dance genres: ballet, modern dance, and Chinese Tang Dynasty dance.

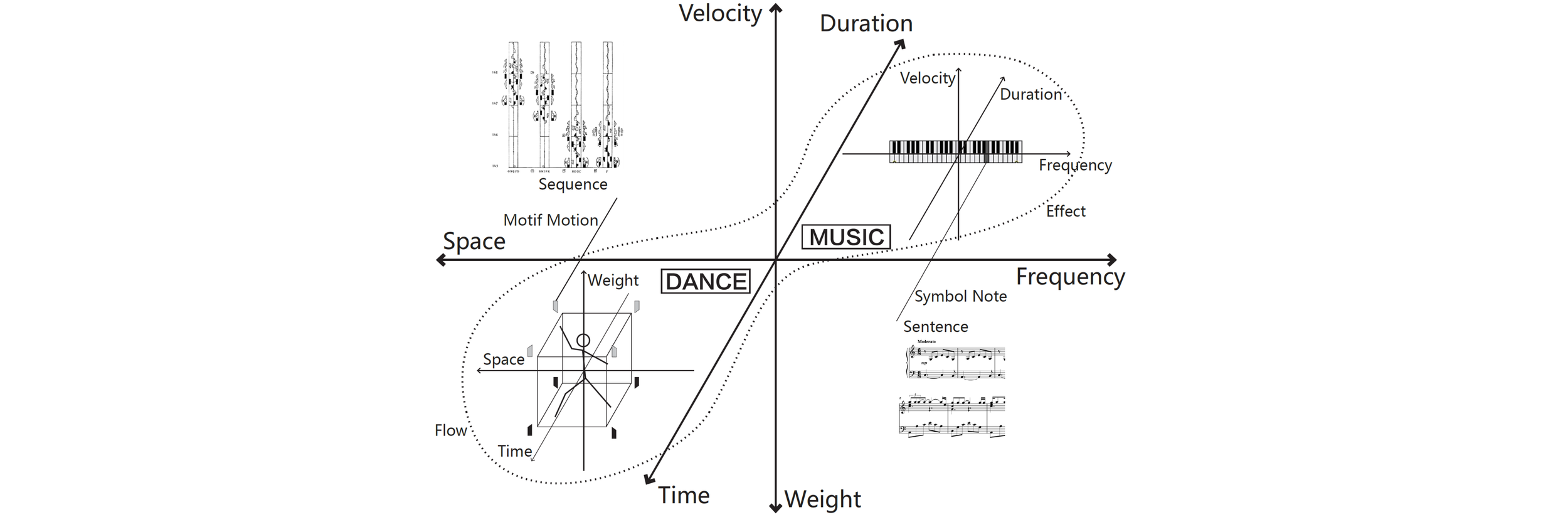

Fig. 1. Corresponding elements in dance and music.

2. RELATED WORK

Choreography. Many have explored how algorithms and machine learning could engage with choreography. Since the 1960s, Merce Cunningham applied new computer software and motion capture technology to choreograph dance in a brand new way [1]. The experimental work by Michael Noll also generated basic choreographic sequences from computers [2]. Some scholars studied choreography from a semiotic aspect and invented dance notations that maintain the authenticity of choreography, which could be further processed into dance learning, practice and research, e.g. Labanotation, Benesh Notation, and Eshkol Wachman Notation. For example,

the Microsoft Labanotation Suite [3] can perform translation between MoCap skeleton and Labanotation, which enables robots to learn to dance from observation.

Music Composition. Algorithmic composition has had a long history for hundreds of years [4]. With the development of technologies used in the art field, people have started to apply more advanced programming methods to music composition to support creative purposes. For example, the HPSCHD system established by computer scientist Lajaren Hiller for composer John Cage, which is influenced by chaos theory, assists in making music elements move away

from unity [5]. Another example is OpenMusic, a visual programming language for computer-assisted music creation developed by Tristan Murail and his team to support the development of spectral-based calculations in music composition. It enables interesting mathematical algorithms to provide fascinating sonic outcomes [6]. The third example is MaxMSP, which provides basic Markov Models and generative grammars for music creators to generate their ideas.

Dance-Music Interaction. Recent advances in algorithms have also enabled dance synthesis from music data. For example, by analyzing the beats and rhythms in a video, researchers can create or manipulate the appearance of dance for better synchronization [7, 8]. State-of-the-art datasets like AIST++ and deep learning architecture like transformers also pushed the boundaries of dance synthesis, producing realistic dance motions matching the input music [9, 10].

Fig. 2. System design of DAMUS

3. SYSTEM DESIGN

DAMUS is based on the corresponding relationship between dance and music: space and frequency, time and duration, weight and velocity, flow and effect (Fig. 1).

The inputs of symbols and notes will be analyzed as creative constraints. Based on motion pattern selection and mapping pattern execution, with further evolutionary computation and style transferring, DAMUS will generate new variations of dance and music pieces as a foundation for collaboration. Artists could then manually select the ones they want (Fig. 2).

This system can be jointly used by multiple users, or by a single user and another media resource in the system.

4. METHODOLOGY

4.1. DANCE MODULE

4.1.1. ENCODING RELATIONSHIPS

The first step is to translate a human figure to an abstract notation system. We can get an animated skeleton from the MoCap of human figure dancing, and map it to Labanotation through Microsoft Labanotation Suite, where we further highlight 13 body parts and joints. This process could also be done by a trained dance notator, and scholars have created a bunch of Labanotation documents on performances in the past century. In Labanotation, each body part is drawn onto a specific column, and we can set an encoding execution to create a number notation sheet, noting each of the body parts at a specific time (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Digitization process of dance moves. For example, code 10 on the right hand in the spatial visualization indicates that the dancer should move the right hand forward.

4.1.2. ALGORITHM-BASED RE-CHOREOGRAPHY

As the performance (musical) piece could be cut into paragraph, sentence, bar, beat, timecode (e.g., 1/2 beat), and the dance notation and music notation aligns timely, we decompose the Labanotation into timecodes with specific composition

of body part condition. For simplicity, we include 27 still directions and 16 turns. In this way, the composition of the condition of each body part at each timecode is written as a series of 13 numbers with a 2-digit number. This could be transformed into a number notation sheet, a sequence of 13-dimension vector for machine learning, or a sequence of point clouds for visualization (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4. Mapping 3D Labanotation to number notation

Fig. 5. Labanotation encoding for body parts

For a specific piece of performance and based on the expression of symbolic Labanotation and its encoding, we could find some patterns of motion elements as P1, P2, ..., Pm, and a series of codes of alternation could be generated as M1,M2, ...,Mn. Some simple M’s come to our mind: mirroring, alternating the step combination when the upper body shares the pattern, alternating the arms when the step combination shares the pattern. Derived from comprehensive dance research and manually picked P’s and M’s, we will develop algorithm to generate more M’s, i.e., keeping the same motif with change in speed and rhythm. At the same time, algorithm will make the decision on the allocation of various mappings applied to the patterns.

4.1.3. VISUALIZATION OF THE RE-CHOREOGRAPHY

After the variation process is applied, we need to find out a strategy to visualize the re-choreography. One way is to apply the reverse process from symbolic Labanotation to number notation sheet in Fig. 3. A trained dance notator or scholar could read the Labanotation and dance it right out. Another way is to communicate our algorithm with the Microsoft Labanotation Suite, through which the variated Labanotation could be translated into an animated skeleton or character, and a dancer could follow the animation and practice.

4.1.4. NEXT STEPS

In a nutshell, the strategy of working with a single piece involves finding motion patterns (P’s) in symbolic Labanotation as well as number notation sheets, and setting mapping patterns of choreography alternation (M’s). When working with a series of performance pieces of similar style, era or creators, the patterns of motions and mappings could be collected together as a dataset, and a compounded algorithm could be applied to select and create new codes from the pool.

We will also add more conditions and randomness to the algorithm for a better computational outcome. Also, solid dance research on specific motion patterns would also benefit the style maintenance during the process of mapping variations. Further on, we consider inviting the original creator or dance groups of the pieces to test the alternated choreography, and iterate afterwards.

Fig. 6. Music digitization process

4.2. MUSIC MODULE

In traditional dance music collaborations, choreographers frequently share with the composer specific pieces of music that they have previously used as sources of inspiration for future compositions. This method, however, is frequently unproductive, particularly in new creative teams or when the composer lacks experience producing music for dance. It is also difficult for the composer to rapidly grasp the choreographer’s vision, and the resulting composition commonly deviates significantly from the dance’s required rhythms. If we would like to solve this issue, we need to make sure the music module can produce musical materials that fit the tempo and rhythm of specific dance genres or moves. Therefore, the first step in developing our dance and music database has been to assess the amount of music that has its own fixed music structure and rules for specific dance genres. For example, in the history of ballet performances, baroque suite music and concerto music have frequently been used in the productions. As a result, we analyzed a large number of pieces in this genre by J.S. Bach, George Frideric Handel, and G. Philipp Telemann, the three most famous baroque composers, who also had the largest num.

4.2.1. DIGITIZATION

The entire tempo and rhythmic model extraction process of all different music genres at this stage, starts with digitizing the score, exporting it to a midi file, transferring the midi file to a JS file, and finally extracting when and how specific music events occur over a set period of time (Fig. 6). When we come across musical pieces that we already have in our midi file collections, the progress could then begin with step three. It does not mean, the music models have to be genre specific, creators could input any possible inspiring musical score as midi or XML files into this system and analyze it as an influential element for the next step.

4.2.2. EXTRAPOLATION AND VARIATION

Moreover, to make use of these influential tempo and rhythmic models the module has extracted earlier from the original sound files, the composer could either use the hidden Markov

method to replace the original pitches with similar baroque music melodies, use a random pitch generator, or morph different musical pitch characters, such as installing jazz music pitches into a baroque music tempo and rhythmic models or other combinations to create fusion outcomes. This is an extrapolation progress with plenty of possibilities. After this part, the module aims reversely transferring the data from the programming stage back to the midi files and musical scores, so the creator could use the materials directly without in-depth coding experiences.

4.2.3. NEXT STEPS

Additionally, because the entire compound system is not intended to supplant the authors’ originality, but rather to assist their needs. The next steps in our working process for the music module will be to provide as many features as possible that allow the composer to edit and influence the outcomes by adding or changing specific sound units, or by constraining the algorithm with specific criteria. For example, setting a specific key signature and pace, quantizing according to time signatures, orchestrating in specific groups of instruments, setting up basic harmonic progressions, and most importantly, relating dance movements to synchronized or nonsynchronized musical contours.

5. CASE STUDIES

5.1. DATABASE SUPPORTED VARIATIONS

The team’s composer, choreographer, designer, and computer scientist have been testing the DAMUS system and trying to come up with new variables as they research. We would like to share two case studies for two different collaborative creation challenges. The first challenge that choreographer and composer team has frequently encountered is the purpose to create a new piece together which is highly referring to the existing data. Therefore, we look at two existing sets of data from our database: a complete music score, a dance score, and a performance video in the ballet and modern dance genres.

These two works both employ Baroque German composer J.S. Bach’s compositions as music, associating with early 20th century American dancer and choreographer Doris Humphrey’s choreography as the dance part. We then try Fig. 7. Corresponding patterns in Air on the G String. to make a different dance-music combination from the input data with a consistent pace and rhythmic model through several stages. For the music part, firstly, we extract the model as it has been addressed earlier. Secondly, we replace the original pitches with the random pitch generator among the midi notes from 1 to 127 and generate three musical pieces, which we call them random A, random B, and random C. It turns out a set of quite interesting results. Since the music is clearly atonal, the musical outcomes have been distinguishable from the original scores even though they are still two musical compositions in a rapid 3/4 pace and an elongate 4/4 pace. We believe they could be quite useful for very experimental creators, but for those who would like the musical materials close to their sources, it could be a bit problematic.

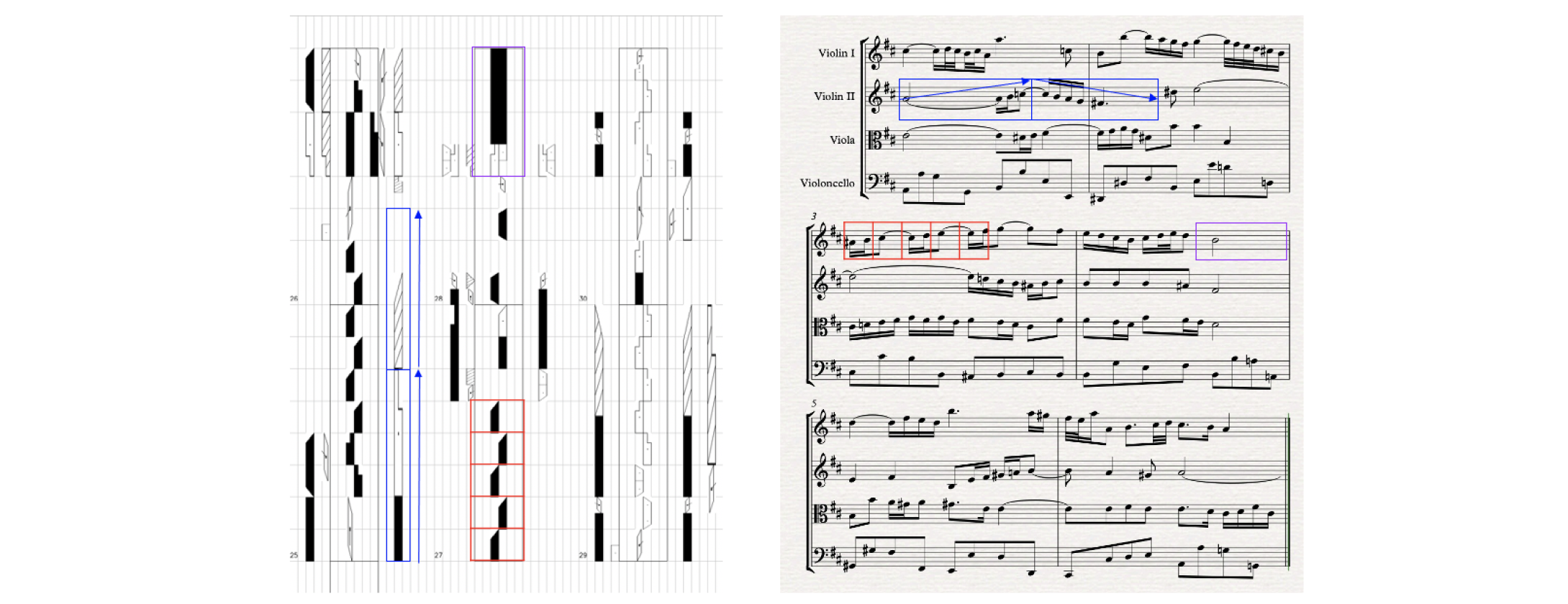

Fig. 7. Corresponding patterns in Air on the G String

Therefore, thirdly, we replace the original pitches with the new set-up pitches that are generated from the original scores by the hidden Markov chain as Markov A, Markov B and Markov C. Additionally, we have set several counterpoint restrictions to avoid two pitches simultaneously happen in minor second, major second, minor seventh, and major seventh intervals, which against the rules of this very specific music genre. Specifically, we set functions to avoid ±1, 2, 10, 11 midi number combinations happening at the same time.

For the dance part, the choreographic variation has been through quite different methods. The music and dance of a modern piece are always related in multiple dimensions, where deep analysis could be applied. One way is to keep the related patterns between music and dance in order to maintain the style of the original performance. For example, in Air on the G String, we have discovered several patterns, such as the elongated stretch, repeated rhythm and contour of ascending and descending (Fig. 7).

Fig. 8. Motion patterns and mappings in Partita

Based on the patterns of motion elements, we move to the physical variation of human bodies. Through analysis of symbolic Labanotation and its encoding, we could set mappings of variations following human kinetics and physical constraints. Take the ballet Partita as example, we name the repetitive patterns as P1 = {(bar1, bar2), (bar3, bar4)} and P2 = {(bar9, bar10), (bar11, bar12), (bar13, bar14)} (Fig. 8). Also, P1 and P2 have the same rhythm, suggesting the possibility of mappings between them. Here we define a possible mapping as M1(P1 ↔ P2) = bar2[body] ↔ bar14[body]. Similarly, we find the repetitive pattern P3 = {(bar23, bar24), (bar25, bar26)}, and we could set another mapping to switch the pairs of bars within P3. Since the support remains the same, this mapping can be defined as M2(P3 ⟲) = bars23,24[arm] ↔ bar25,26[arm].

5.2. CREATIVE CONTINUATION BASED ON ORIGINAL INPUTS

The second challenge that a choreographer and composer team has frequently encountered is to make variations from the raw materials they have already worked on, in order to add another section next to the existing work. In this case study, we take the Chinese Tang Dynasty dance as our genre, and first create an authentic piece without algorithms. This specific dance genre is challenging as it requires in-depth research on the ancient Chinese archives.

Nan Ge Zi is the ancient Tang Dynasty dance piece we have recovered, derived from a and-drawn textual dance notation discovered in the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, China, in 1900, then shipped to France by the French Sinologist Paul Eugene Pelliot and now documented in the French National Library. The study of Nan Ge Zi originated in 1930s, and now the prevailing interpretation was completed by Beijing Dance Academy in 1980s. The scholars deciphered the text into a piece of dance, and recorded it in Labanotation.

Fig. 9. Original and updated Labanotation of Nan Ge Zi

During our study, we first re-analyze the archives and renotate the dance in Labanotation based on the most updated research. Then, we create a dance-music piece with its very specific music instrumentation and dance movements to recover this historical dance as authentic as possible. Afterwards, we utilize DAMUS to generate more variations. For the dance part, since we know from the re-analysis that the piece contains eight main motion motifs, which could be elaborated into four phrases as well as 48 bars composed by 144 beats. From professional choreographers’ perspective, it is reasonable to variate this continued section by changing the positions or recombine the body parts of the beats, bars or phrases with the same motif (e.g., bars 4 and 16 both describe serving wine). The figure shows the comparison between the original and the re-choreography (Fig. 9).

For the music part, the dance music in the Tang Dynasty has very specific instrument preferences, such as Pipa, Dizi, and other percussion instruments. Unlike the piano, these instruments have a limited range of pitches and require historical intonation. Therefore, when we work on the replacement of the original pitches, we carefully restrict the pitch limitation of each instrument and make sure their intonation can be either adjusted by the composer inside of the DAMUS or conveniently downloaded as a midi file and edited in other digital audio workstation (DAW) programs that composers are familiar with. So we could maintain the authentic and unified characters between the original and its continuities.

6. CONCLUSION

Based on fundamental research in dance and music, we have developed DAMUS, a system prototype for facilitating the collaboration between composers and choreographers through mapping algorithms using symbolic and number notations of dance and music. We have made the first steps on the re-composition and re-choreography methodology for ballet, modern dance, and Chinese Tang Dynasty dance. We will test more genres and further develop DAMUS with evolutionary computation and style transfer to generate new iterations of dance and music pieces as collaborative foundations.

7. REFERENCES

[1] Thecla Schiphorst, “Merce Cunningham: Making Dances with the Computer,” Merce Cunningham: Creative elements, pp. 79–98, 2013.

[2] Laura Karreman, “The Dance without the Dancer: Writing Dance in Digital Scores,” Performance Research, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 120–128, 2013.

[3] Katsushi Ikeuchi, Zhaoyuan Ma, Zengqiang Yan, Shunsuke Kudoh, and Minako Nakamura, “Describing Upper-Body Motions Based on Labanotation for Learning-From-Observation Robots,” International Journal of Computer Vision, vol. 126, no. 12, 2018.

[4] Gerhard Nierhaus, Algorithmic Composition: Paradigms of Automated Music Generation, Springer Science & Business Media, 2009.

[5] Larry Austin, “HPSCHD,” Computer Music Journal, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 83–85, 2004.

[6] Jean Bresson, Carlos Agon, and G´erard Assayag, “OpenMusic: Visual Programming Environment for Music Composition, Analysis and Research,” in Proceedings of the 19th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 2011, pp. 743–746.

[7] Abe Davis and Maneesh Agrawala, “Visual Rhythm and Beat,” ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG), vol. 37, no. 4, Jul 2018.

[8] Yang Zhou, “Adobe MAX Sneaks: Project On the Beat,” https://research.adobe.com/video/project-on-the-beat/, 2020.

[9] Kang Chen, Zhipeng Tan, Jin Lei, Song-Hai Zhang, Yuan-Chen Guo, Weidong Zhang, and Shi-Min Hu, “ChoreoMaster: Choreography-Oriented Music-Driven Dance Synthesis,” ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG), vol. 40, no. 4, Jul 2021.

[10] Ruilong Li, Shan Yang, David A Ross, and Angjoo Kanazawa, “AI Choreographer: Music Conditioned 3D Dance Generation with AIST++,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp. 13401–13412.

4

XingQi · Consciousness

Role: Director, Producer, Media Artist 2022.6 - 2023.3

XingQi Series are created during the Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum Art Residency, featured at “Imperial Kiln Universe, Mysterial of Blue and White” Special Exhibition, 2022 IRCAM FORUM at NYU, 2022 Hangzhou Binjiang International Dance Festival, and the Permanent Collection of the Imperial Kiln Museum.

XingQi · Consciousness is a multimedia and site-specific dance film combining classical aesthetics and contemporary media techniques. The choreography, playwright and composition are based on the historical research of the imperial kiln factory, the unearthed ceramic gene bank and blue-and-white porcelain craftsmanship, as well as the performance space of the imperial kiln museum and the cultural relic site. Through the dialogue between body language, projection mapping and camera movement, the performance connects the material, space, media art and spirit, interpreting the imperial kiln aesthetics of the broken and eternal, and the spirit of tenacious, distant and romantic.

Visual Content of Body Movement, Chinese Calligraphy, Blue and White Porcelain, created with Stable Diffusion

Motion Graphics, created with GAN (Generative Adversarial Network)

Multimedia Performance in Cultural Relics with Projection

5

Invisibody and CyberTogetherness

Lead Artist: Anna Borou Yu Collaborators: Irina Demina, Jiajian Min 2021.4

Featured in RECONNECT Online Performance Festival, 2021 Asia Digital Art Exhibition, Hermes Creative Award 2022 Platinum Winner

Invisibody is an interactive multimedia virtual performance during the pandemic. By guiding the audience through the media stations generated from body motions, the performance questions the relationship between body and space, physical and virtual, tangible and invisible.

Is any “body” here?!?

We want to invite you to unite with us in the virtual space, wander through a series of embodied cyber existence, and mediate the poetic experience of the virtual world through our physical bodies.

“A body's material. It's dense. It's impenetrable. Penetrate it, and you break it, puncture it, tear it...A body's immaterial. It's a drawing, a contour, an idea…”[1] Voice, segment, silhouette, skeleton, avatar, emoji… We are real, and constructed. We are here, and there. We are different, and identical. Every “body” we meet in this virtual togetherness, is an invisible face of the real body from each of us. A body can speak, think, dream, imagine… The INVISIBODY is free to sense and flow, beyond time and space.

[1] Jean-Luc Nancy, Indices 1&5, Excerpted from ‘Fifty-eight Indices on the Body’

CyberTogetherness is a virtual performance premiered at YET TO .COM(E) International Online Residency. With broadcast software as the stage, we brings together a variety of imagination and media about the body. The real-life body, as the subject of dancing, is captured as the silhouette by Kinect, performing in the virtual space as the background. This is accompanied by a pre-recorded voice-changing monologue that triggers the parameter changes of real-time music input.

For dancers, this is choreography of the body. The concept of the body is deconstructed and reconstructed; for tech artists, it is a choreography of media. The body is merged into the ocean of media. The set trajectory traverses the ocean and time difference through the networks with emotions, bringing delay/error/uncertainty and impromptu expressions. Meanwhile, this performance is also a process of mixing backstage and frontstage. When we open the black box, is it a transparent system or another black box? Is what you see really what you get?